Nobel lecture

From Ph.D. to Nobel Laureate

Discoveries made by PhD students rarely result in a Nobel Prize, but this is what happened to Donna Strickland, whose groundbreaking work in laser physics ushered in not only a new understanding of physics but also optimised mobile phone screens and improved people’s vision.

By Kristoffer Frøkjær

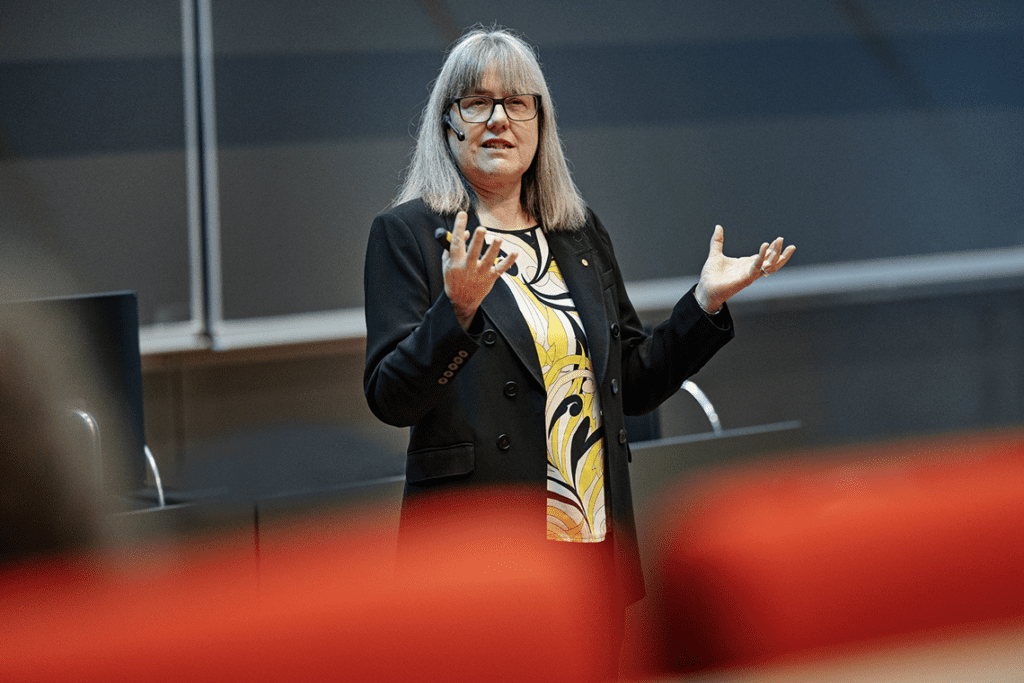

The auditorium is packed to the brim. From the back row both ponytails and balding crowns are visible in the audience. Strickland appeals to young students and the old alike, which highlights the purpose of the Royal Academy’s Nobel lectures: to give a wide audience the opportunity to hear the best scientists in the world. Strickland is unique, but not only because of her Nobel Prize:

“Even though the Royal Academy has hosted more than 21 events like this in collaboration with the Novo Nordisk Foundation since 2011, it’s the first time we welcome a woman to the stage,” says Professor Thomas Sinkjær, Secretary General of the Royal Academy, in his welcome to the Nobel Prize winner.

A splendid union of applied and basic research

On the stage a middle-aged woman is gesturing animatedly:

“In my talk I’d like to discuss both applied and basic research – so let’s start by going back 150 years in time. Back then we didn’t know whether a photon was a particle or a wave. Today we know it is both.

But getting this far required the intervention of both Einstein and Planck. And it wasn’t until as late as 1960 that we got the first laser – despite the fact that Einstein already laid the mathematical foundation back in 1917. Laser light is different from ordinary light from a light bulb, for example because it can be pointed in a specific direction. The discovery of the laser had an enormous impact and led to major breakthroughs up to the 1980s. But then a standstill occurred because the light in lasers at the time could not be made stronger without destroying the laser itself.

1.4 km instead of 2.5 km

But then Strickland and her supervisor at the time, Gérard Mourou, stepped in. At this point Strickland shows a photo of herself – a noticeably young version from 1983 – in front of the laser she worked with some 40 years ago. It consisted of a large coil of fibre optic cable.

“Light had to be transmitted throughout the 1.4 km of cable in that coil. People always ask: ‘Why exactly 1.4 km of cable? Why did you use 1.4 km of cable for the experiment that led to a Nobel Prize?’”

With her usual sense of humour, she continued:

“People think that to win a Nobel Prize, everything has to be 100% well thought out. I originally had 2.5 km but it broke. So the answer to why 1.4 km is that that’s where the cable broke. I always mention this because it’s the nature of science to find solutions to the problems you encounter in your research. And even when you do things wrong, you can still win a Nobel Prize.”

The technology she developed using the 1.4 km of cable, and all the other technical hardware, broke the boundaries of what was possible with laser technology at the time. Suddenly, it was possible to create light that was a thousand times stronger than before and to knock electrons off atoms. This opened up new opportunities for understanding the physics around us and for major basic research discoveries. But the discovery of a new type of laser light has also been used, for example in eye surgery, where ultra-short pulses have improved the vision of millions of people, and in materials science, where laser pulses can create, for instance better smartphone screens.

The future: From light to matter

To conclude her lecture, Strickland looked into the future. Historically, since the 1960s, the intensity of laser light that can be emitted has continually increased. Today it is around a quadrillion times stronger than the first lasers. And this development will continue, predicts Strickland:

“Fantastic facilities exist now in both Europe and South Korea. And the intensity of laser light will continue to grow so that one day – maybe not just around the corner, but one day – we will be able to turn light into matter. When that happens we will have completely new opportunities available for understanding the world around us,” she concludes and is greeted by loud applause from the audience.

The Royal Academy has arranged Nobel Prize lectures since 2011 in collaboration with the Novo Nordisk Foundation. This lecture was held at the University of Copenhagen.