Nobel Prizes

Nobel Prize Day: Danish recipients and what they can teach us

Since the Nobel Prize was first awarded in 1901, Denmark has had 14 recipients, nine of whom were or are members of the Royal Academy. Rats, chickens and cockroaches have all featured in an enduring and compelling story of love, war and scientific ideals.

By Ghita Nidam Møller

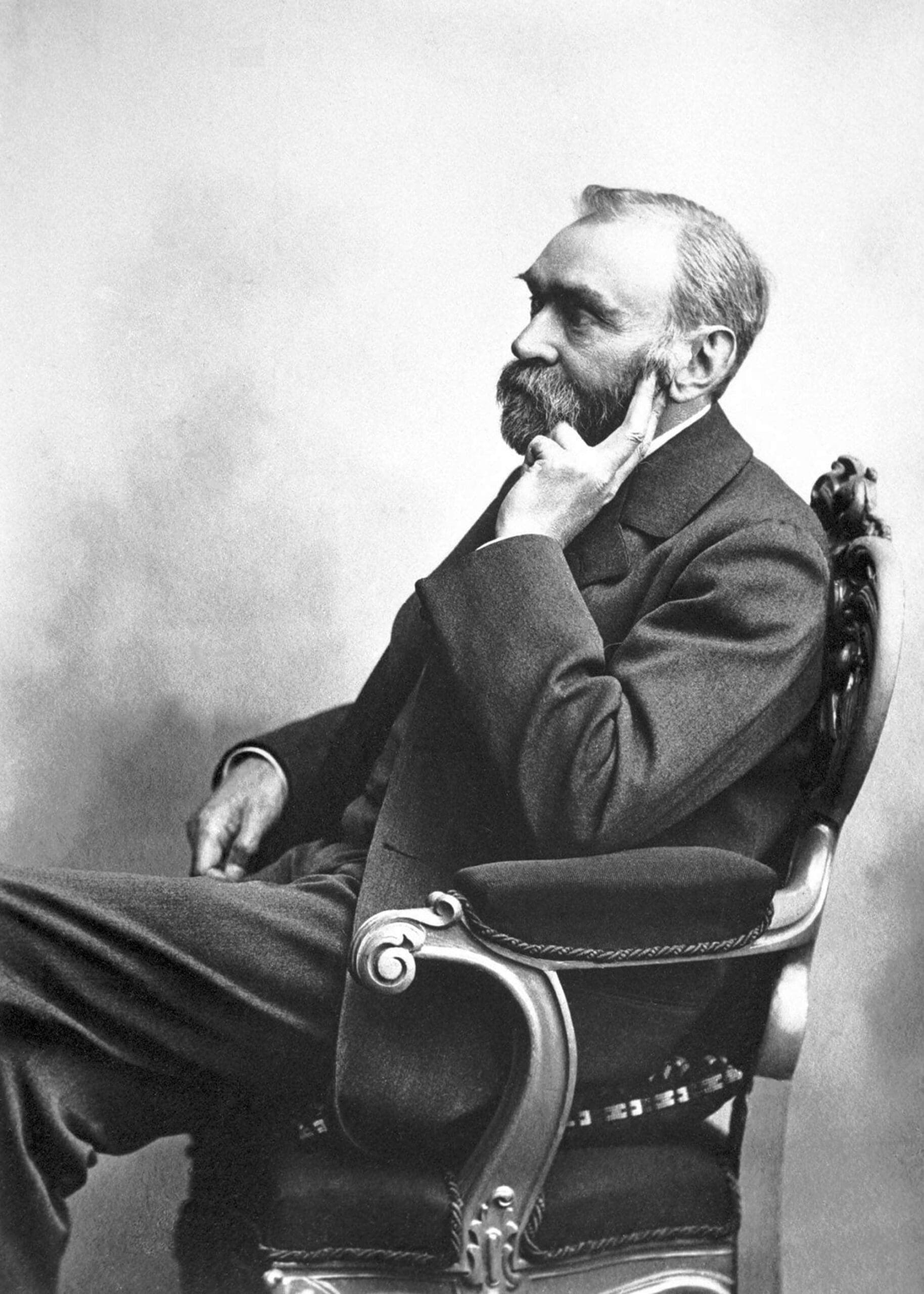

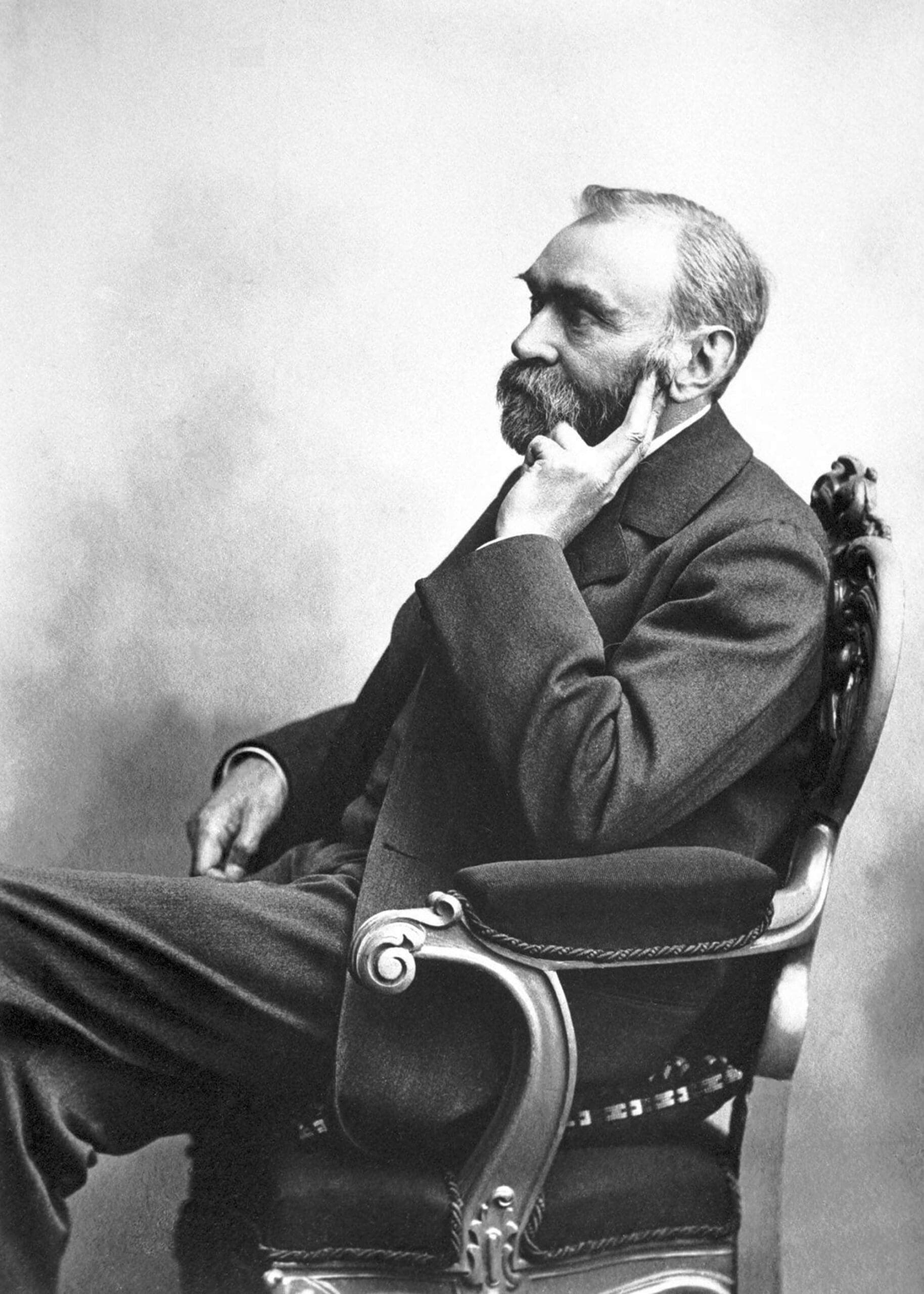

Polyglot, engineer, chemist, entrepreneur, industrialist, author and holder of 355 patents. A tumultuous and literally explosive life’s work that cost a younger brother his life, all in the space of just 63 years.

The famous engineer, chemist, scientist, lover of literature and “merchant of death” Alfred Nobel left us long ago. This is not news. But the passion the father of dynamite had for science across disciplines lives on. Thanks to Nobel’s will, the pioneers of science are celebrated every year on the anniversary of his death, 10 December, and this year is no exception.

That’s why the red carpet is being rolled out in Stockholm, Sweden this year and has been every year since 1901. The Royal Academy’s 208-year history has witnessed a cavalcade of scientific adventures. Honoured for leaving their mark on their own era and the future, nine of Denmark’s 14 recipients of the Nobel Prize were or are members of the Royal Academy.

Their discoveries and stories say more about our times than you might realise.

Death, war, love and nonconformism. In a work of fiction the prize winners would have played thinly disguised lead roles in a wild tale running the gauntlet from espionage and the nuclear race to cockroaches, chickens and the phenomenal success of Novo Nordisk and Wegovy®, the latest world star on the market. The beacons of the past are a constant, chosen in accordance to Nobel’s will for securing the greatest benefits for mankind.

A look back in time shows that the Royal Academy’s award-winning members have much to teach us.

Dilemmas of the past are catching up with us

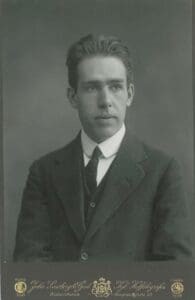

Niels Bohr’s role in history raised questions that still resonate today. For example, should scientists take responsibility for their research, or is it the responsibility of those who use the research?

The physicist’s story transcends fiction at a time when powerful candidates lined up as the nuclear arms race raged and the world spilt in two during World War II. In the midst of the chaos, Bohr exhibited the very essence of the Royal Academy, of which he later became

president. He was more than just an unrivalled scientist and the 1922 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics for his theory of atomic structure. Albert Einstein also reportedly called him the most intelligent scientist of his time, which is quite a compliment.

Bohr was likewise a citizen of the world with the unwavering belief in the open exchange of opinions and knowledge across borders. In addition to hampering Soviet espionage he saved Jewish and Russian scientists. He was ultimately forced to choose sides. As is well known, the US won and he became part of the Anglo-American Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower personally bestowed on Bohr the first Atoms for Peace Award, which lauds the development or application of peaceful nuclear technology.

In many ways science is once more being challenged by similar dilemmas as war and conflict escalate. The invasion of Ukraine is dividing the world again, while cybersecurity threats, dual-use technology and espionage haunt universities. Growing Danish and international investment is also setting the stage, with Denmark most recently joining the US, like Bohr in his era, by signing the Artemis Accords, a common set of principles spearheaded by the US for the peaceful exploration of deep space.

Science and researchers play an indisputably leading role in society and that’s part of their legacy. This is also the case with the Nobel Prize in Physics, where Bohr’s son, Aage, succeeded his father in multiple ways. Aage’s research, which was a natural extension of his father’s, threw him headlong into his father’s world. While in exile in the US in 1943, the father and son were also associated with the Manhattan Project. Together with Danish-American physicist Ben Mottelson and American physicist Leo James Rainwater, Aage received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1975 for their exploration of the structure of the atomic nucleus.

Equally admired is Aage’s belief conducting open and peaceful science. Like his father Aage, he was honoured with the Atoms for Peace Award, and later the H.C. Ørsted Medal, the Ole Rømer Medal and the Rutherford Medal. The Bohr legacy lives on in Aage’s three sons, two of whom are currently members of the Royal Academy.

Under the skin and out of the box

They range from being world renowned to under the radar. Biochemist and civil engineer Henrik Dam and physician and immunologist Niels K. Jerne expanded our understanding of what happens under the skin and were awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1943 and 1984, respectively.

Dam is the oft-unseen hero of haemophiliacs, whose condition means that the body’s ability to clot blood is impaired. Consequently they need extra assistance to stop any bleeding and vitamin K does the trick. We can thank Dam and his experiments with a group of chickens for this discovery.

Jerne also studied our internal system, applying theories that dared to challenge existing dogma about antibodies. Specifically he paved the way with three theories that have powered how we currently understand and define our immune system. He left his mark on the world as a true globetrotter who, through collaborative research, put immunology on the world map and challenged the hierarchical structure of the scientific community.

From 1956–1962 he was head of the Sections of Biological Standards and of Immunology at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland. He later took up professorships in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, US and in Frankfurt, Germany, positioning him as the leading international immunology theorist of the time. He also went on to head the Basel Institute for Immunology in Switzerland, which became an international centre for immunological research.

To learn more about the individual Danish winners of the Nobel Prize use the hyperlinks on their names to access Lex, which is Denmark’s national encyclopaedia (in Danish only). Timeline: Ghita Nidam Møller. Photos: Royal Academy Archives

More than love, more than Novo

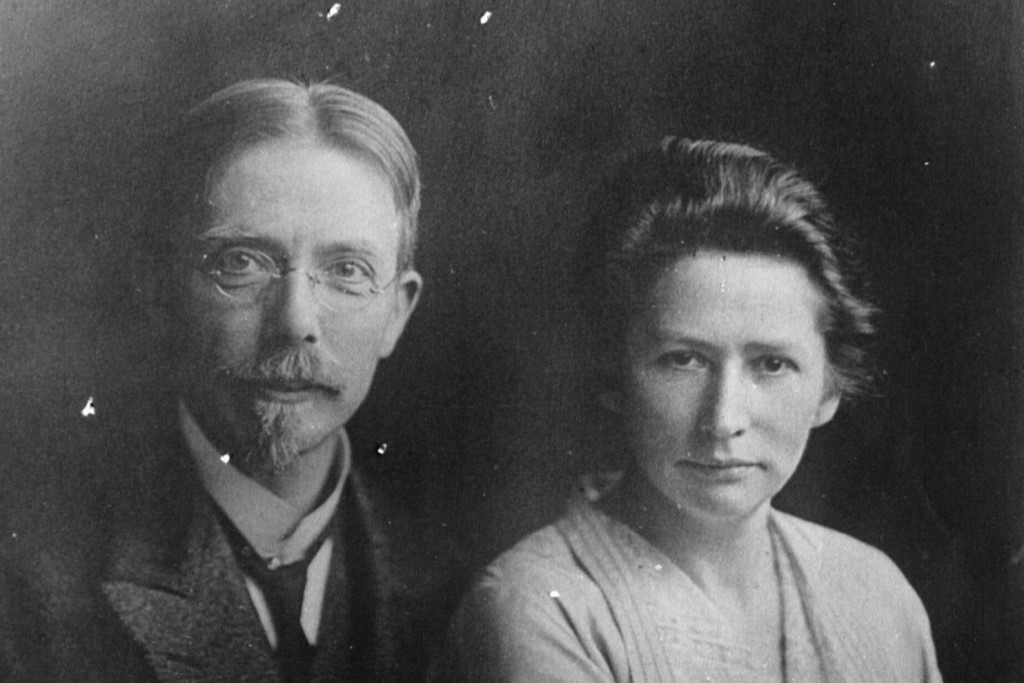

You can’t mention August Krogh without including Marie – even though only the husband in this couple received the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology in 1920. The two scientists, colleagues and spouses formed a unique duo whose achievements continue to echo around the world. As a result the Royal Academy eagerly celebrated the 150th anniversary of the couple’s births.

Basically, without the Kroghs, there would be no Novo Nordisk today. What is more, they also proved and are a favourite justification for free thinking, experimental ideas, insisting on methodological innovation, and interdisciplinary collaboration. This may sound pompous but the proof is self-evident – perhaps you already know the story.

Marie Krogh is historic in her own right as Denmark’s fourth female medical physician. Moreover, she was a significant part of the powerhouse behind her husband’s success. His work as a skilled inventor, physiologist and professor of zoophysiology, with Marie at his side, proved to be a perfect combination for understanding the body’s need for insulin and developing the first diabetes medicine.

In brief, as early as 1922 August obtained exclusive rights to manufacture insulin in Scandinavia, which led to its initial production in Denmark. This development represents a highly significant precursor for the many breakthroughs leading to the development of the first Novo insulin and today’s roaringly successful weight-loss drug Wegovy®.

The Krogh’s story concerns more than just the history of Novo Nordisk and insulin. Today August Krogh is regarded as one of the founders of work and exercise physiology, thanks in part to both Marie and his experimental spirit – not to mention the ability to explore. They had immense freedom, the unpredictability leading to a truly amazing journey that laid the foundation for the generation of some of Denmark’s greatest wealth.

Popular rock star revitalises the research policy debate

The achievements of Nobel Prize winners have become scientific milestones but also part of the research policy debate. Physician and physiologist Jens Christian Skou won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1997, giving him a platform to highlight that a key issue was long-term immersion underpinned by a strong framework.

Almost eerily, Skou aptly described the gist of today’s policy debate on issues concerning uncertainty and innumerable job changes for many young researchers, countless funding applications, and endless sector research appointments. He also argued in favour of increasing independent research funding for universities to avoid earmarked grants. Now, almost 30 years later, the same discussion is taking place about the balance between independent and strategic research.

Our most recent Nobel Prize winner, Morten Meldal, has not been shy about emphasising the role of independent research because an accidental reaction and coincidence led to the discovery of click chemistry in the Carlsberg Research Laboratory – and with it the first Danish Nobel Prize in a quarter of a century.

Meldal has stressed that his 2022 Nobel Prize is a tribute to creative freedom, immersion, excellent facilities and the entire team of PhDs, postdocs and professors who were involved in the original project. The award has once again put science in the spotlight.

They found enlightenment and rats

Spreading enlightenment has been the Royal Academy’s mission ever since King Christian VI issued an edict in this regard in 1743. Niels R. Finsen took this declaration quite literally, landing him Denmark’s first Nobel Prize in 1903.

Finsen’s heart was set on finding new treatments using ultraviolet light but from a young age a heart condition prevented him from joining the medical profession. It nevertheless gave him the opportunity to devote himself to researching and developing new treatments for especially cutaneous tuberculosis – a dreadful disease that can co-occur with tuberculosis in the internal organs. Finsen discovered that light was the solution.

He made a major breakthrough by discovering carbon-arc light therapy, also called Finsen therapy, which turned him into a hero and led to being awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology in 1903. He died the following year but his legacy lives on in the Finsen Institute in Copenhagen, which bridges the gap between the first light institute and contemporary cancer treatment. Two decades later, in 1926, the Danish doctor Johannes Fibiger became the first cancer researcher to win the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Fibiger is purportedly the first person to use rat experiments to prove that external factors can cause cancer. His somewhat repellent experiment involved feeding rats cockroaches with a roundworm, which led to stomach cancer that spread to the lymph nodes and lungs.

His observations have since been called into question but inspired a new era of studies on carcinogenic effects. The experimental phase also points to the future, the focus of the methodological approach challenging not only what we know but also how we know it, and with it the possibility of replication testing. Some experiments to avoid repeating, however, are Nobel’s own experiments during the development of dynamite. Accidents occurred on several occasions but the one that hit him hardest personally was an explosion at a factory that claimed the life of his younger brother.

Like Nobel, the story is colourful, sometimes dangerous and continues to this day. Thank you and congratulations on today, Alfred. Rest in peace as the world turns.

How we know what we know: The Nobel Prize website, Danmarks Nationalleksikon Lex (use the timeline to learn more), the University of Copenhagen website, an interview in Science Report and an interview with the director behind the documentary Niels Bohr: The world’s best human being”.

Photo: Atelier Florman, Nobel Foundation Archives

In the footsteps of Alfred Nobel

Nobel was a Swedish inventor, entrepreneur, scientist and businessman who also wrote poetry and plays. The six original Nobel Prizes reflect his diverse interests and are a worldwide honouring of outstanding achievements in physics, chemistry, physiology, medicine, literature and working for peace. The Nobel Prize in Economics has since been added.

Nobel inherited his broad interest in science from his father, who was a wealthy businessman involved in the manufacturing of arms. Nobel’s education involved the study of the natural sciences, literature and multiple foreign languages. At the age of 17 he already spoke five languages fluently.

His career was dedicated to experiments with nitroglycerine and developing dynamite, a scientific achievement that proved to be both a profitable and dangerous business. He established over 90 factories and laboratories in more than 20 countries and held 355 patents.

His success, however, came at a cost. An explosion in 1864 at the family-owned factory in Heleneborg, Sweden killed his younger brother Emil and four others.

Nobel never had children and left the bulk of his assets to establish the Nobel Prize in his last will and testament in 1895. After his death, the Nobel Prize was awarded for the first time in 1901 on 10 December, the anniversary of his death.

The will states that four of the prizes must be awarded in Stockholm, Sweden, while the Nobel Peace Prize must be awarded in Norway by a committee appointed by the Norwegian Parliament.

Source: Lex – Danmarks Nationalleksikon and Nobel Prize.